Moniker of an Eatable

This is your political legacy, Bob Ney. This and a 30-month sentence for corruption charges. Nice. Photo from Take Part.

A rose by any other name is still a rose, but shouldn’t we think about why are we trying to avoid the word rose? The words we use have power. Names shape the view of that which it refers. A huge part of this power is in how unassuming names can be. Generally people don’t analyze the name of something to which they were just introduced. We accept names. It isn’t until much later that one might really think about the implications of names and naming and how they direct people’s thinking (including one's own) about something. Those in power often assign names, thus reflecting their perspectives. This only serves to perpetuate their own power by creating a structure wherein they decide what has value, allowing them to retain their power. It’s basic physics, really; an object in power tends to stay in power.

There are myriad examples of these kind of situations, but a few jump out. In 2003 France believed that weapons inspectors in Iraq should be given more time, thereby disagreeing with the American and British opinions to move to war in the region. Representative Bob Ney, R-Ohio, served as chairman of the Committee on House Administration and decided that french toast and french fries should be renamed, substituting french for freedom. The change was made official in the cafeteria menus in House office buildings in Washington. It wasn’t until three years later that the menus began listing french fries and french toast again. Ney explained that the name change was a “small, but symbolic effort” to show the anger that many felt toward France.

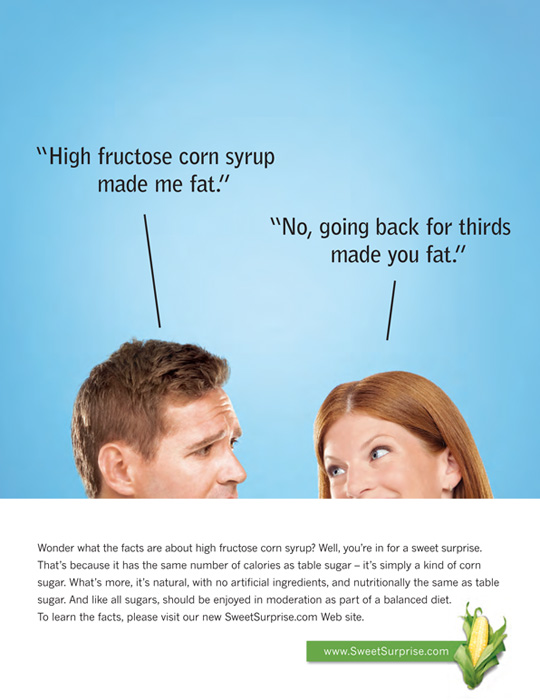

More recently, we see the power of names being used by agribusiness. High fructose corn syrup (HFCS) has a bad rap; we all know that. In 2010, the Corn Refiners Association tried to rename HFCS to “corn sugar.” It sounds a little more natural, and you know, what’s the difference between cane sugar and corn sugar? The whole point was to have a name that sounds less my-food-was-made-in-a-lab-with-vats and more my-food-was-grown-outside-and-is-completely-natural-not-processed-at-all.

The problems with the proposed renaming was 1) corn sugar already referred to corn dextrose, 2) the name implies a crystalline solid but HFCS is, you know, a syrup, and 3) HFCS is made in a lab with vats, 4) the name change could lead to reactions from anyone whose body is unable to process fructose, 5) the name “corn sugar” implies that the consumer and their body is already familiar with it and therefore can’t blame it for health problems related to its consumption. So, it turns out there’s a lot in a name. A whole lot.

Also maybe eating something that was made in a lab probably can’t help things? Also being told that it’s natural even though it is highly processed and refined, simply by a name would probably make this even harder? Photo by Corn Refiners Association.

Maftoul, pearl couscous, Israeli couscous, giant couscous, moghrabieh, or fregola; all arguably the same thing, but why so many names? According to Yotam Ottolenghi, a famed Israeli-born British chef, the names vary by region. He’s not wrong, but he doesn’t acknowledge the politics of using any of the names. By using one name, the speaker in some ways erases the existence of the other regions and their histories. Calling it pearl couscous or middle-eastern couscous, as my own local health food store labels it, depoliticizes the food, but only on the surface.

Instead of talking about the issue at hand, we’re avoiding it altogether. If a food has a history, so does the name we use to identify it. With an item like this, however, there is no one name that is attributed to it consistently and historically. Each name connotes something different, privileging different powers over one another and reinforcing different values of various cultures. However, the most familiar name may be Israeli couscous which reinforces a power dynamic in the region and repeatedly gives Israel the privilege of owning the name. The same would be true if the product was consistently called moghrabieh, the Lebanese name, but because Lebanon does not have the same resources that Israel has, the most common name reflects that. In other words, it reflects the current power structures.

This photo, taken as part of Saveur's feature called "The Heart of Palestine", shows the process of making maftoul from scratch. The recipe I followed to make maftoul was part of this feature. Photo by Saveur.

Every food we eat is a political choice. Sometimes the choice has to do with farmers’ rights, biodiversity and agricultural practices, or, as in this case, the historical roots of a food and the cultures steeped in controversy from which they come. No matter what you eat or how you eat it, your food sends a message. Just as your food can erase, your food can create acknowledge. Just as your food can mask the almost universal presence of agribusiness, it can also expose it. Just as your food can silence a group or a people, it can also start a conversation about why they are being silenced and the power structures responsible.

Palestinian Maftoul

The recipe took about two hours for me to complete. It was well worth it. I made a conscious decision to make an unaltered version of the recipe published by Saveur, reprinted below, because who would know how to make maftoul better than the Palestinian women featured in the article? Not I, that’s for sure.

Maftoul as I prepared it. Photo by Liv Anderson.

- 8 whole allspice, plus 1⁄8 tsp. ground

- 2 cloves garlic, peeled and crushed

- 1 (3 1⁄2-4-lb.) chicken, quartered

- 2 medium yellow onions, 1 halved, 1 minced

- 1 stick cinnamon, plus 1⁄8 tsp. ground

- Kosher salt, to taste

- 3⁄4 cup olive oil

- 2 1⁄2 tsp. ground cumin

- 1 1⁄2 tsp. ground cardamom

- 1 cup maftoul (Palestinian large-grain couscous)

- Freshly ground black pepper, to taste

- 1 (15-oz.) can chickpeas, drained and rinsed

- 1 1⁄2 lemons, thinly sliced

- Greek yogurt, for serving

- Roughly chopped parsley, for garnish

Bring chicken, whole allspice, half each the garlic and lemon, the halved onion, cinnamon stick, salt, and 8 cups water to a boil in a 6-qt. saucepan. Reduce heat to medium-low; cook, covered slightly, until chicken is cooked, 15–20 minutes. Using tongs, transfer chicken to a bowl. Add 1⁄4 cup oil, half the cumin, and the cardamom to the chicken and toss to coat; set aside. Increase heat to medium; simmer until stock is reduced to 4 cups, 20–25 minutes. Strain, discarding solids, into a bowl.

Heat 1⁄4 cup oil in a 4-qt. saucepan over medium-high heat. Add remaining garlic and lemons and the minced onion; cook, stirring occasionally, until golden, 6–8 minutes. Add ground allspice and cinnamon, the remaining cumin, the maftoul, salt, and pepper; cook, stirring, until couscous is lightly toasted, about 4 minutes. Add 1 1⁄2 cups reserved stock; boil. Reduce heat to low; cook, covered, until couscous is tender and all the liquid is absorbed, 16–18 minutes. Uncover, fluff with a fork, and transfer to a serving platter; keep warm.

Heat remaining oil in a 12" skillet over medium-high heat. Add chicken, skin side down; cook, flipping once, until browned, 5–7 minutes. Transfer to platter with couscous. Add chickpeas to skillet with remaining stock; boil. Cook until liquid is reduced to about 1⁄2 cup, 8–10 minutes. Spoon chickpeas over chicken; garnish with parsley and serve with yogurt.

This recipe was first published by Saveur in December of 2013. You can find the original recipe here.

Works Cited

Ettinger, Jill. “High Fructose Corn Syrup vs. Corn Sugar.” Huffington Post, December 1, 2011. Accessed April 5, 2016. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/organic-authoritycom/hfcs-corn-sugar-rebranding_b_984092.html.

“FDA rejects industry bid to change name of high fructose corn syrup to ‘corn sugar.’” CBSNews, May 30, 2012. Accessed April 17, 2016. http://www.cbsnews.com/news/fda-rejects-industry-bid-to-change-name-of-high-fructose-corn-syrup-to-corn-sugar/.

Jenkins, Nancy Harmon. “In the West Bank a good harvest and a shared meal are at the center of an enduring culture.” Saveur, December 10, 2013. Accessed March 30, 2016. http://www.saveur.com/article/travels/heart-of-palestine.

Loughlin, Sean. “House Cafeterias change names for ‘french’ fries and ‘french’ toast.” CNN, March 12, 2003. Accessed April 5, 2016. http://www.cnn.com/2003/ALLPOLITICS/03/11/sprj.irq.fries/.

Ottelenghi, Yotam. “Yotam Ottelenghi’s maftoul recipes.” The Guardian. April 16, 2013. Accessed March 30, 2016. http://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2013/apr/26/maftoul-couscous-recipes-yotam-ottolenghi.

Patel, Raj. Stuffed and Stavred: The Hidden Battle for the World Food System. New York: Melville House Publishing, 2007.

Shah, Riddhi. “10 tragic moments in food propaganda.” Salon, June 10, 2010. Accessed March, 30, 2016. http://www.salon.com/2010/06/11/food_propaganda/.

Silver, Alexandra. “Top 10 Dubious Name Changes.” Time, March 28, 2011. Accessed April 5, 2016. http://content.time.com/time/specials/packages/article/0,28804,2061530_2061531_2061545,00.html.

“What is Israeli Couscous?.” CookThink. Accessed February 2, 2015. http://www.cookthink.com/reference/2176/What_is_Israeli_couscous.

Wilson, Bee. “The Kitchen Thinker: Renaming food.” The Telegraph, November 2, 2010. Access April 5, 2016. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/foodanddrink/8085387/The-Kitchen-Thinker-Renaming-food.html.