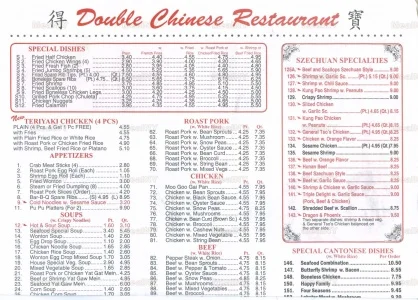

The quintessential/stereotypical Chinese menu. From MealNY.

“Let’s get Chinese food tonight.” What do you wear? Whatever you’ve got on, right? But if someone were to say “Let’s go for French food tonight?,” you would probably do a quick mental run through of your closet to figure out what to wear and oh crap, do we have a reservation? There’s an assumption upon which both answers are based. Chinese food is cheap, French food is expensive. But not all Chinese food is cheap, and not all French food is expensive.

When we make these kind of assumptions we are in essence evaluating cultures and peoples, usually unfairly and often based on a simplistic version of an entire region or country. The idea of one singular cuisine in China is pretty ridiculous. It’s a big country with lots of regions and lots of cuisines. Food in Guangdong province is different from food in Sichuan province is different from food in Fujian province is different from food in Yunnan Province. The comparison between Chinese and French foods is a clear example of the biases we have based on oversimplifications. But just because this is the comparison I’m using doesn’t mean they are the only cuisines that this applies to. What about Polish food, or Thai? Brazilian? Mexican? Ethiopian? Indian? Italian?

The transcontinental railroad was built by immigrants from China as well as other countries. From Geisel Library.

The prices that we associate with various cuisines is a minor but impactful form of discrimination based in history. When immigrants from China moved to California in the mid-1800s, the type of work that they were allowed to do was limited to hard labor and select positions in the service industry, such as laundries and the chop suey houses that multiplied during this time. Chop suey houses in particular were a way for the Chinese immigrants to make a business niche for themselves in which they weren’t criticized for taking jobs from European-Americans. It was inexpensive, but seen as exotic. However, chop suey was an americanized version of a dish found in parts of rural China. By contrast French restaurants represented something entirely different. By going to a French restaurant you were aligning yourself with the European aristocracy, something that merited a higher price. It wasn’t just about the food and being fed, but the way that eating French food was an exercise of one’s privilege. Chinese food was cheap because few saw a value in it beyond just the food.

Apparently this is what we aspired to. From Kashmir Company.

While these roots might have made more sense at the time of the gold rush, it’s pretty absurd that we still see these price associations and all of the assumptions that they carry with them to this day. New York restaurateur and chef David Chang wrote about the price assumptions around the time Momofuku Nishi opened, saying,

I’m done with people telling me that I can’t charge what I want to charge for things.

The only difference between these dishes is price point and regionality. Most people don’t know what su jae bi is. Most people do know what chicken and dumplings is. But there’s a weird cost association that if it’s Asian, it has to be cheap. But we’re making our own chicken broth. We’re making our own noodles. It’s a labor-intensive dish.

It pisses me off that Asian food has to be cheaper. Why? Not one person has given me a reason why. All the ingredients that we’re getting are top quality, and just as expensive as any other restaurant….Don’t tell me that I can’t charge like Italian food.

From "Inside Momofuku Nishi," Lucky Peach, January 8, 2016.

David Chang in the kitchen. From Momofuku.

When there’s an assumption that Chinese food should be cheaper than French food, or Asian food should be cheaper that European food, there’s an underlying message. While it’s subtle, the message itself is discriminatory. According to the price associations, there’s nothing that anyone wants to align themselves with in Chinese culture. It’s pretty absurd that so many assumptions can be communicated based on price, but they are. We don’t have to abandon our favorite inexpensive Chinese go to, but there is no reason why we David Chang’s 17-course tasting menu at Momofuku Ko should be met with outrage when the price is increased to $451 for two, while no one bats an eye at Thomas Keller’s 8-course tasting menu price of $583 for two at the French Laundry. Why can’t we value a chef like David Chang at the same level as we value Thomas Keller of the French Laundry?

https://momofuku.com/our-company/team/

Pork Dumplings

Pork Dumplings. Time consuming. Whole night blocked out for this. Pork Dumplings. Pork Dumplings.

4 cups of all purpose flour

1 ⅓ cup water

1.5 lb ground pork

½ cup grated ginger

2 cups fined chopped scallions

½ cup soy sauce

2 tbs rice wine

2 tps white pepper

1 egg

Mix the dough and water until it forms a scraggly mass. Knead the dough until it becomes a smooth ball of dough (about 7 minutes). Cut into small rounds (about a tablespoon) and roll into balls. Roll out as thin as possible but still opaque.

Mix ground pork, ginger, scallions, soy sauce, rice wine, and white pepper together (hands are easiest, but like do you). Test a small portion of the pork mixture by frying it in a small pan. Adjust soy sauce and pepper to taste. Mix egg into pork mixture.

Take one dough round in the palm of your hand and place a heaping tablespoon of the pork mixture in the center. Run a finger dipped in water around the edge of the round. Press the opposite sides of the round together, folding in one side as you go. There are lots of styles and techniques you can use, but as long as it is sealed, you’re good. Make sure the dough is completely sealed by pinching the edges.

Bring a pot of water to a rolling boil. Gently drop several dumplings into the water, making sure that they have room to move along the bottom as they cook so as not to stick. When the dumplings float, they’re ready.

Alternately, bring an oiled pan to medium heat and place dumplings into pan. Add ½ cup water to the pan (watch out for steam) and cover for 5 minutes. Don’t touch them. They’ll do their thing and everything will be great.

Enjoy.

Bibliography

Gabaccia, Donna R. We are What We Eat: Ethnic Food and the Making of Americans. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1998.

Haley, Andrew P. Turning the Tables: Restaurants and the Rise of the American Middle Class, 1880-1920. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: The University of North Carolina Press, 2011.

Ji-Song Ku, Robert, Martin F. Manalasan IV, and Anita Mannur, ed. Eating Asian American: A Food Studies Reader. New York, New York: New York University Press, 2013.

Lee, Jennifer 8. The Fortune Cookie Chronicles: Adventures in the World of Chinese Food. New York, New York: Twelve, 2008.

Liu, Haiming. From Canton Restaurant to Panda Express: a History of Chinese Food in the United States. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 2015.

Magnini, Vincent P., and Seontaik Kim. “The Influences of restaurant menu font style, background color, and physical weight on consumers’ perceptions.” International Journal of Hospitality Management 53 (2016): 42-28.

“On the Ubiquity of Chinese Restaurants.” The Economist. May 7, 2008. Accessed April 26, 2016. http://www.economist.com/blogs/freeexchange/2008/05/on_the_ubiquity_of_chinese_res.

![A news article helped consumers understand how the ration point system would work to better prepare them for using them wisely. [image courtesy of Ames Historical Society]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/56a3d77e9cadb6769969b4a2/1456517894374-1RIDK7D3NNBP64D3AW7N/image-asset.jpeg)

![Above is a sugar purchase certificate and some of the explanations for the sugar rations as issued by the Price Administration. [Images courtesy of the Ames Historical Society]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/56a3d77e9cadb6769969b4a2/1456518154227-BC186TG8YHKYRMQKCCML/image-asset.jpeg)